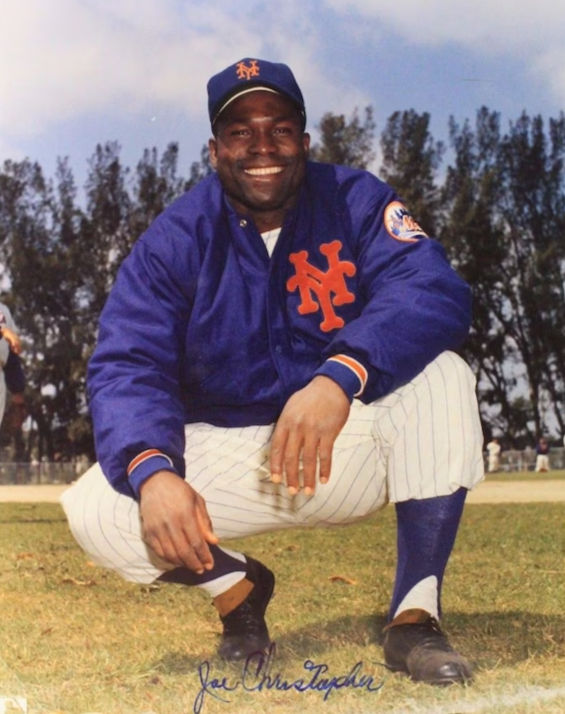

Mets Sunday School: Forgotten Faces of Flushing #9: Joe Christopher: The Virgin Islands Pioneer Behind the ‘Yo La Tengo’ Legend

- Mark Rosenman

- Mar 2

- 5 min read

Welcome to the ninth installment of Mets Sunday School: Forgotten Faces of Flushing, where we take a trip down memory lane to revisit the orange-and-blue-clad players who time—and often Mets fans—seem to have forgotten. Every week, we’ll rummage through baseball cards (or crumbling programs that smelled like hot dogs) to shine a light on the Mets who didn’t make headlines but still found a way to be part of the team’s unpredictable and unforgettable history at Shea, Citi, the Polo Grounds, and beyond.

Last week, we examined the legacy of Rube Walker—not as a player, but as the architect behind one of the most revolutionary pitching strategies in baseball history. Walker, though never stepping up to the plate for the Mets, played a crucial role in molding the pitching philosophies that would define the franchise’s greatest successes.

This week, we turn our attention to a player who did step up to the plate—one of the original 1962 Mets, Joe Christopher. Before there were Cleon Jones and Tommie Agee, before Darryl Strawberry and Brandon Nimmo, Christopher was out there in the early days, hustling in the outfield and wielding a bat for a team that was more lovable than it was successful Often overlooked in the franchise’s history, his contributions—and his journey to the Mets—deserve another look.

So grab a seat, sharpen your pencils, and let’s get to work!

Joe Christopher’s journey to the majors was anything but ordinary. Born on December 13, 1935, in Frederiksted, St. Croix, he was part of a baseball-rich island that produced several major leaguers including New York Yankee Horace Clarke. His father oversaw a mango and cane plantation, while his mother kept their large family running. Joe, the youngest of six, grew up playing baseball on dusty fields and dodging rogue grounders with his local team, the Annaly Athletics.

At 18, Christopher found himself on a team traveling 3,129 miles to Wichita, Kansas, for the National Baseball Congress tournament. It was there that Pirates super-scout Howie Haak spotted him and decided the speedy Virgin Islander had major league potential. At first, Joe balked at Haak’s offer—after all, the post office paid better—but baseball won out. By 1959, he became the first native Virgin Islander to make it to the majors, joining the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Christopher was more than ready for the big leagues, though his first few years were spent as a backup outfielder for the Pirates from 1959 through 1961. He first got the call-up when Roberto Clemente was sidelined with an injury, and his major league debut came on May 26, 1959, during one of the most famous games in baseball history—Harvey Haddix’s 12-inning perfect game against the Milwaukee Braves. The game ended in the 13th when Joe Adcock’s deep drive cleared the right-center field fence. Christopher, who was patrolling right field at the time, later recalled speculation that Clemente might have been able to snag the ball, but he dismissed the notion: “It was well over the fence. I don’t think even he could have reached it.”

Though Adcock’s hit initially appeared to be a three-run homer, the official scoring turned it into a one-run double due to a baserunning blunder by Hank Aaron. Aaron mistakenly thought the game had ended as a result of a ground rule double and when the first run scored, peeled off toward the dugout, and was subsequently passed on the base paths by Adcock. As a result, Adcock was credited with a double instead of a home run, and the Braves were awarded a 1-0 victory in the box score. Despite the controversy surrounding the final play, Christopher’s role in the game remained a memorable footnote in baseball history.

Christopher’s early years in the big leagues were spent as a backup outfielder for the Pirates, where he earned the nickname “Hurryin’ Joe” thanks to his blazing speed. He even played a small role in the Pirates’ legendary 1960 World Series victory over the Yankees, appearing in three games and scoring twice.

Despite his talent, the Pirates never saw him as a full-time player, and after three seasons of sporadic playing time, he got his shot at everyday action when the Mets selected him with the fifth pick in the 1961 expansion draft. It cost them $75,000—a hefty sum for a team that spent most of its time in the bargain bin.

Still, Joe had to wait for his moment. He spent parts of 1962 and 1963 bouncing between the minors and the Mets’ bench, most notably finding himself at the center of the famous “Yo La Tengo” incident. A bilingual man of the world, Christopher tried to help center fielder Richie Ashburn communicate with shortstop Elio Chacón by teaching him the Spanish phrase for “I got it.” The plan worked—right up until the moment Ashburn got steamrolled by left fielder Frank Thomas, who apparently didn’t get the memo.

That incident may have been humorous, but Christopher’s real moment arrived in 1964, when he finally got his chance to play every day. Given a full season in the lineup, he flourished, putting together one of the finest offensive seasons in Mets history at the time. He played in 154 games, hit .300, and set career highs with 16 homers, 76 RBIs, 163 hits, 26 doubles, and eight triples. On August 18, he torched his old team, the Pirates, for two triples, a double, and a home run in an 8-6 Mets win.

Then, on September 25, Christopher etched his name into Mets history again. Facing the Cincinnati Reds at Shea Stadium, he broke up Jim Maloney’s no-hit bid with a second-inning single. It was the only hit the Mets managed all game, as Maloney settled for a 3–0 one-hit shutout. Though the Mets lost, Christopher’s ability to spoil a no-hitter reinforced his knack for rising to the moment.

Christopher’s hot bat cooled in 1965. A finger injury set him back, and with rookie Ron Swoboda waiting in the wings, his time in Queens was running out. After the season, the Mets traded him to the Red Sox for Ed Bressoud. He had a brief stint in Boston before being shipped to Detroit in a package that included pitcher Earl Wilson. Though he never played for the Tigers, he had left his mark on the game, finishing with a respectable .260 average, 29 homers, and 173 RBIs over eight seasons. His speed, glove, and bat all had their moments—but it was his colorful journey through baseball’s odd corners that made Joe Christopher one of the more memorable Forgotten Faces of Flushing.

Though his time in the spotlight was brief, Joe Christopher’s legacy as a pioneer for Virgin Island ballplayers and as an early contributor to Mets history deserves recognition. He exemplified the scrappy, underdog nature of those early Mets teams, proving that even in the leanest years, there were players worth remembering. Baseball is full of stars, but it’s also built on the shoulders of those who hustled, adapted, and made the most of their moment. Christopher was one of them, and his story is worth telling.

Next week, we dust off another name from the Mets’ attic. Stay tuned!

Comments